Let us all be Pragmatists

2023-10-16

Every once in a while, I hear people talking about high-level languages as a way to not be practical and/or pragmatic. As an example, this week such a situation occurred — I heard someone saying something along those lines about Haskell. They see the added abstractions as a way to add fanciness for the sake of fanciness into your project, without any logical practical reason for doing so.

Ever since I understood why programmers left assembly languages behind, I understood that this popular take is nothing more than just a misconception on why we seek new concepts. In fact, this has a lot to do with one of my previous posts, Don’t be a Hero, join a League, because there I am proposing indirectly that having those new tools as a partner for development is more practical. In this post, I will go further by showing that it is exactly because we want to be more practical that we seek new layers of abstractions.

Definitions

Let us start by settling on a definition of what it means to be pragmatic and practical:

Pragmatic: dealing with things sensibly and realistically in a way that is based on practical rather than theoretical considerations.

Practical: of or concerned with the actual doing or use of something rather than with theory and ideas

The popular take from this is that if there is a breach between what the theory says, e.g., type theory, set theory, category theory, relational theory, etc, and what we can do to deliver something by acting or doing, executing the latter would be called a pragmatic or practical act. The oversight in such an evaluation comes from the absence of the consideration of time being spent in its entirety.

When dealing with projects, there are deadlines that need to be met. Hence, there is a constraint in how much time we have at our disposal in order to deliver our artifact. Such requirement dictates what and how we classify as practical/pragmatic or not. You may ask yourself: “Does the judgment change depending on how much time we have available?”. The answer is an enormous YES.

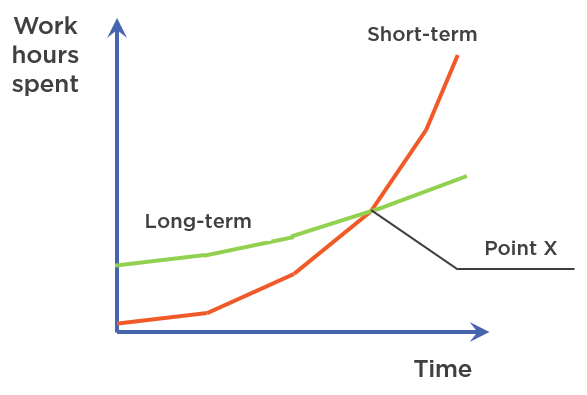

The reason is simple: assuming that the project survives long enough time, the weight of present decisions will heavily affect its future development. If the project ends in a week, there isn’t much incentive to consider the best of the best maintenance practices and there is even less motivation to make a very granular and in-detail documentation. As the time window for development expands, we start to regret bad decisions that, at the time were practical, but cost us future practicality. And it gets worse with time; stakes get higher every single month the project lives and new features are added. Something that you see as convenient and practical for a one-day-only hack can spread out and become your worst nightmare in a matter of weeks. In summary: the life span of a project prescribes how much we should consider the implications on future development, hence the notion of practicality also depends on the complete time window.

In fact, the relationship between time and practicality is so strong that you pay twice if you don’t respect it. You pay once when your current impractical decision impacts the foreseeable future implementations and you pay once again when you change your mind. If you notice the bad decision in time before the product’s demise, you will have to retroactively pay for refactoring the existent artifact. Such a daunting conclusion can make turning around into better more practical tools impractical, due to the potentially astronomical amount of time that the snowball effect will demand to get things back on track.

Expressiveness

Aside from projects getting longer and more complicated with time, there is another reason why we decided to level up our programming languages: they provide us more expressiveness, i.e., they provided us better ways to express our problems in a way that better maps the problem with our understanding of its solution.

The classic example is messing with pointers in C. When you contemplate the solution to manipulate lists in your mind, there is an extra step required to map that to C when using pointers. You gotta map the denotational semantics of your solution, which is the meaning of the solution, to its operational semantics, which is how the tool that you are using executes such abstract concepts in its feature set. This process can not only be tiresome due to the difference between those two types of semantics, but it is also one of the greatest sources of bugs in software. It is not always trivial to see how can we map a pure idea to be adequately represented in our tool of choice and its mechanisms. This was the major nightmare when using assembly languages for complex applications: the amount of mapping was completely out of question and error-prone due to how far apart the solution and its implementation were.

What we want is a tool that reduces the gap between those two, in order for us to spend as little time and effort as possible on this mapping and have available resources to tackle more problems or refine our solution. Every single second spent in mapping one onto the other has nothing to do with the actual solution but with tooling limitations and/or performance concerns.

Hence, the pinnacle of practicality is having a 1:1 correspondence between the universe of solutions, abstract and usually mathematical ideas, and the universe of tooling, which we use to materialize such ideas. Thus, the creation of high-level languages was a big deal precisely because their proposal was to make this mapping closer to the ideal scenario in contrast with their counterparts, e.g., assembly languages.

Legacy

Given those reasons, it may be intriguing to answer the question: why do so many people see high-level stuff as just perfume that adds no value? The reason is simple: legacy cannot be ignored.

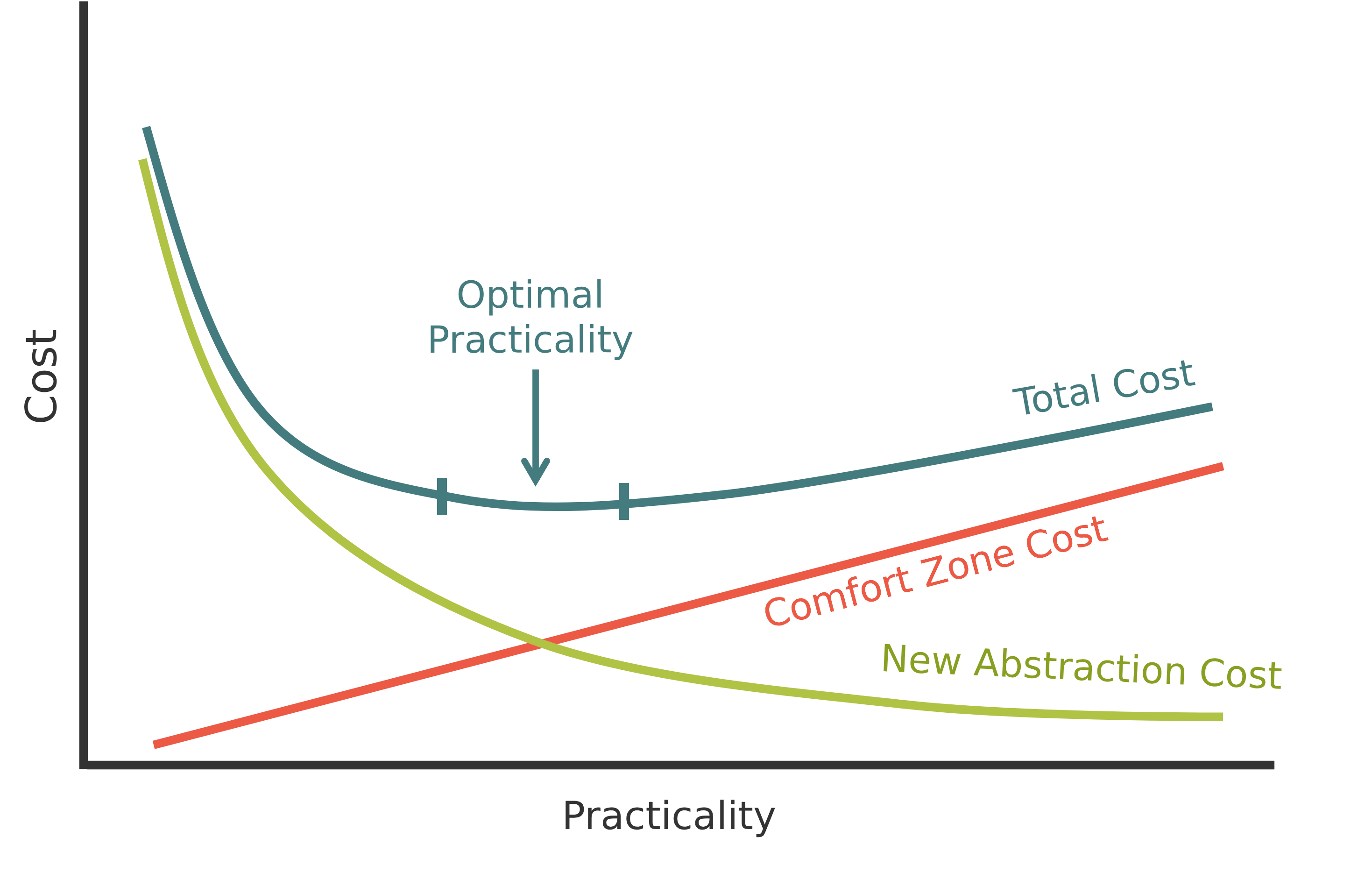

As you know a tool more, and put more hours into it, you will consequently have more practice with it. Going back to our definition, we see that having more practice implies having one more practical reason: I used it more, hence I know more about it, hence I have more experience interacting with it, hence I can do it faster. If you completely ignore thinking about future maintenance, there is some truth to this argument. If there is no future, you value doing it in a faster manner in a way you are already familiar with, especially given that no long-term maintenance will happen at all. And, because you practiced more, you may be also fast in mapping denotational semantics to operational ones in the blink of an eye.

This, however, can lead to a problematic semantical situation: practical/pragmatic will start to be used as a synonym of conservative. It will be more about doing things in a way you are already accustomed to, rather than being practical in its totality. You will try to argue that doing what you have done a thousand times will always be more practical than actually being open-minded to even more practical solutions.

Mr. Churchill’s quote, once again, explains the situation perfectly:

We shape our buildings, thereafter they shape us.

Education

The answer to combat Churchill’s conclusion is to educate ourselves. Let us not be fooled by our comfort zone and think that “If it works, it is enough” and

“I have done this a billion times, it must be the best”. The process of improvement necessarily involves touching a chaotic plane of existence. Quoting Jordan

Peterson:

The ideal place is to be right in the middle between Order and Chaos. To have enough Order to feel tethered, but enough Chaos to be challenged and learn new things. This is where meaning is to be found. In other words, push yourself to the limit of your ability and challenge yourself.

I’m not saying this is an easy task. Allowing yourself to breathe a different air is something that involves courage. Considering that the new tool may be better than what you already know involves humility. Such virtues are hard to acquire and require a lot of effort to be truly mastered.

But you would be at least trying to be better. You will not be trapped into the idea that because something is “set in the industry’s stone” it is necessarily more practical and/or pragmatic. Rather than popularity, use something much better: reason. It is by reason that the fanciness for the sake of fanciness is reaped and purposeful choices are made. Rationally understand if this is truly more practical considering the life span of the project and if it improves the bridge between what we want to solve and how we will solve it.

Having the ability to judge if exploring something different/new is worth it during a specific time window given a certain deadline is usually mastered when reaching seniority level. Maybe something from the 80s, which would be unforeseen to you and the team, can be the most practical solution. Only after you understand that what is trending usually does not fall into the aforementioned notion of practicality that your eyes start to open to both directions of history. You start to look forward to both old and recent solutions because both can be categorized as new based on your experience and knowledge, hence they have the potential to better accommodate your needs.

Innovation

One of the threats that this simplification of practicality poses is a direct threat to innovation. When a new tool or idea comes around, conservative developers will be the first ones to point fingers at it and just blast it with unfounded accusations of being fancy for the sake of being fancy and adding no value to real-world applications. They will say things like “No real project uses it” or “I can do the same with X”.

The former accusation is a natural fact from a new tool, it is because it is new that nobody of a significant size is using it yet. The latter accusation is even worse: most of the time, nobody is talking about being able to do something that the others can’t. Until someone discovers something more powerful than Turing Machines or Lambda Calculus, there is no power difference between such tools, because all of them have been proved to be equivalent in power. New tools propose a much better question: how much extra practicality do they bring to the table?

When a new technology is brought to the market the question should not be: “What can it do that the others can’t?”. The question should rather be: “Will I be able to accomodate/express my needs better with this?” or “How much better will this be to maintain for the next decade?”.

Technologies such as functional programming, static type systems, databases based on a relational model, borrow checker, etc, are examples of options that promise you better ways to express your intention/model, especially if it involves constraints along the way (most of the time it does), alongside better maintainability. Their selling point is to capture people who see as more practical not having to deal with underwhelming denotational semantics, run-time errors/bugs, constraints polluting the application layer, and state machines managed chaotically.

It starts to get foggy to assess practicality when the dimension in which a tool claims to be more practical is different than the dimension of a competing tool. Both can fulfill your goal to some degree, but they may do that in different axes of interest. You may have better semantics to describe your problem, but that may come with a penalty in readability which implies a penalty in maintainability. So, when a situation involves trade-offs, it is up for the developer/team to indicate priorities to each axis in order to properly evaluate which aspect will carry more weight when judging practicality.

Conclusion

This unilateral take on practicality, viewing it as a short-time investment heavily based on legacy, is a trend that hurts everybody. Computer science students study old solutions during university and later suffer a technology crisis when they join the industry world. Experienced developers are locked into old tools, purposely blinding themselves to potentially better solutions because they are afraid of “theoretical” things and abstract ideas. Long-term companies are losing money because their professionals are not thinking about future proofing the company in its totality.

And there is no way around it: we gotta fight this twisted view on pragmatism and practicality. We can join the debates and explain to those that are willing to listen to the reasons why this new solution is the real pragmatic take on it. But that won’t be enough. The ultimatum will be to become the real and total pragmatists. Let us all make companies thrive with what better fits the future of the project and makes a better connection between our elegant, mathematical, and theoretical solutions and our mundane, material, and technology-based tools.